Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in 2025

- Sean Stambaugh

- Jul 15

- 23 min read

Invitation for Feedback and Disclaimer

Today I am going to share my extended thoughts on what the DEI landscape looks like in 2025. In the spirit of humility, I welcome critical conversation and feedback about the thoughts shared here. Sometimes in this post I use language that I am aware is problematic; I do so sparingly, and I am placing language like this in quotes, using it for the sake of understanding across a spectrum of prior knowledge that exists on these topics.

-Sean

Our Current Moment: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in 2025

There’s a lot of learning to do from our current moment and the history that got us here. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) is a fraught topic in 2025, as DEI has been:

Performatively embraced but sabotaged in (in)action

Co-opted with “cancel culture”

Essentialized into buzzwords that prompt highly varied reactionary responses

Tokenized into flashy marketing graphics and splashed across corporate logos

Targeted in political discourse

Memeified into “woke” culture

Excised financially and ideologically in federal and many State governments

Outright banned down to the level of certain books themselves (we’ve already been down that path, as have others in history…)

(Re)dumped onto the shoulders of those without the privilege to just “drop it”

Strategically codified into less recognizable language

Pushed back behind closed doors

The cumulative result is that the DEI waters have been trampled repeatedly, leaving them cloudy at best and divided into separate muddy puddles at worst. A lot of this has been deliberate, and we’ve seen this tactic before; creating confusion is a good way to sew doubt and fear.

It happened to Critical Race Theory (CRT) not too long ago, despite the fact that Critical Race Theory has existed as a term for over 35 years, and the ideas behind it had been brewing much longer. There weren’t alarm bells about CRT outside of some academic dissent (after all, it’s largely a legal theory) until it was politically and financially expedient for there to be some timely fearmongering in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd. Then, CRT was muddled and turned into a convenient scapegoat deployed by dominant power. After that, many people began to forget that the “Critical” in the term “Critical Race Theory” is the exact same “Critical” that exists in the term “Critical Thinking.” As somebody who has dedicated their life to education, I have to hope that we still value critical thinking, but I digress.

This politicking of language is deliberate and destructive, and it’s a part of what has happened to DEI. A lot of time, money, and energy were poured into creating confusion and fear about what DEI actually is, and these efforts were highly effective at manipulating peoples’ perceptions. People really believe(d) that DEI was being used to justify conducting so-called “sex change operations” in classrooms. This feels absurd—it is absurd—but if we take the universally person-centered and humble approach, we need to look for empathy and understanding. For that, let’s start our search by turning to history.

Looking to History

History has taught us repeatedly that fear sews division and factionalist allegiance, often leading to conflict, especially when issued from an authoritative bully pulpit. This pulpit could be a political podium or a mainstream media press briefing or religious sermon, or, as is so categorically easy to do today, a colorful Twitch studio or FaceBook livestream or self-published “news site.” The Nazis used this fear-based tactic against Jewish people in the leadup to the holocaust, the Belgian Colonizers used it to consolidate power against the Tutsi and Hutu peoples in Rwanda, and it’s a strategy that’s been used countless times across history and the planet to target immigrants, as it clearly is being used today.

Not to be trite or insensitive to the horrors of these examples, but instead to show just how widespread and effective the tactic of using fear to sew division and consolidate factionalist allegiance is:

Technology companies have used it: the Apple vs. PC commercials played on primal fears of being accepted as cool (I may be dating myself here, but remember the commercials with Justin Long – “I’m a Mac,” “…and I’m a PC.”), and it worked with lasting impact to this day; my gamers out there will be thinking about Xbox vs. PlayStation and the fear of not being able to play with your friends.

Cleaning companies have used it: during the COVID pandemic, cleaning companies like Lysol and Clorox leaned hard into their superiority at killing viruses over other options; Lysol’s market share rose by 5% from 2019-2023.

It’s a widespread strategy that occurs at multiple levels of society, and it obviously operates today in 2025, where even the word “immigrant” is starting to feel like it simply means “undesirable” and has less to do with somebody’s country of origin. Fear sewing division and factionalist allegiance by exploiting language.

In public discourse in the last few years, the term “DEI” has also drifted further and further away from what the letters actually stand for, as it’s been sloganized into thinly veiled racism like “DEI-hire” or slathered in corporatized branding and design that is vacuous of any real meaning.

The reason this vicious strategy shows up time and time again is because it is effective. It plays on the nexus of evolutionary psychology, the survival need for belonging, and the plastic nature of language. Blurring language and meaning and truth allows the non-threatening to become very threatening, very quickly. It works when products are the target, it works when ideas are the target, and it works people(s) or communities are the target. It can happen at any time, but people are especially susceptible to being swayed by these tactics when they are already under fear or pressure or stress—the so-called Shock Doctrine.

This is certainly what has happened to DEI, because so much of the conversation around it is inflated hyperbole completely removed from what the words Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion really mean and teach. And it’s a real shame, because I believe that most people actually support what DEI is truly about, as opposed to the trampled and spun and fearmongered understanding that many have today.

What DEI Actually Means: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Diversity is a simple recognition of the fact of human experience: that individuals, peoples, communities, and cultures have variety among them. It’s non-controversial and universally true. This variety exists across skin color, language, gender, physical attributes, beliefs, practices, values, and just about any other descriptor you could name. Diversity does not mean “just minorities,” it includes everyone. Making a ham and cheese sandwich with mayo on white bread is just as much of a cultural practice as making Frito pie, jollof rice, or matzah ball soup.

If folks are struggling with the idea of diversity itself, deep self-awareness work is usually required, including working to improve understanding of implicit bias and potentially working with a counselor or therapist. We’re not here to individually judge why some people might hold prejudices against certain identities; doing so is not helpful. We hope that we can agree fundamentally, however, that all human beings have dignity, regardless of who they are or their story. Folks who struggle with this concept likely require outside assistance beyond what training alone can provide.

Equity calls on us to recognize that equality as a practice counterintuitively does not live up to its egalitarian ideals. This is simply because while people are equal in value and dignity, we’re not equal in our experiences of life; again, not controversial, and universally true.

Equality inadvertently asks us to forget both history and happenstance, assuming everyone starts from a totally level playing field, which is tempting and comforting for some of us to do, if we have the privilege to be able to do so. Ignoring uncomfortable realities is no way to learn and grow, though, and so we have to consider how and why we live in a society where people in our world encounter unbalanced advantages and adversity, and usually a complex mixture of both, because of their background and identity (or intersectionality). Instead of treating everyone exactly the same and difference as taboo, or blanketly ignoring other ways of being entirely, equity acknowledges difference as a source of strength and opportunity. It recognizes that if people are empowered according to their need—yes, unequally—we all stand to benefit by being lifted up together. Most people already subscribe to this idea to some extent; we understand why things like parking spaces for disabled people exist and why students with different educational needs have Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). We’re pretty much fine with allergy and Kosher and gluten free and vegetarian labeling.

Compared to the examples above, some people struggle more with the idea of equity when it’s applied to pieces of identity like race or gender or sexuality. This has to do with complex histories of pain, colonization, guilt, shame, indoctrination, deferral of accountability, and, for some, much more simple and outright bigotry. But equity unapologetically asks us to embrace the truth of the Lottery of Birth: none of us chose our own identities; we didn’t get to fill out a survey in the womb determining our race or gender or sexuality or language or disabilities or allergies or anything else, including what accidents or achievements or injustice or luck we might celebrate along the journey of life. And that is something that we do all share equally. With this understanding of birth, the illusion of choice, and difference, it becomes a lot more difficult to target certain identities or communities, because we just as easily could have been one of “those people.” Being careful to avoid stereotype, there are countless documented cases where race or socioeconomic status or geography/rurality or other elements of identity are directly tied to structural barriers and other forms of oppression. For evidence, simply look to the Social Determinants/Drivers of Health (SDOH) and the state of education here in New Mexico.

If folks are struggling with the idea of equity, coming from an empathetic standpoint, that makes sense. Our schools mostly taught us the myth of equality, the bootstraps mindset runs deep in pieces of American culture and society, and equality does appear have noble intent and underpinnings; it’s also a lot more intuitive to understand than equity. Somehow equality just feels fairer, even though it’s not.

The best antidote here is increased experience and shared storytelling with people from diverse backgrounds, those unlike us, combined with room for affinity and belonging with whomever our own communities consist of. This requires safe, culturally responsive, and ongoing space for learning from and about others and ourselves. There’s an oscillation, a rhythm, to growing our understanding of equity. This rhythm asks for cultural humility and being sensitively attuned to self and others, with high emotional intelligence and empathy. It takes time and practice, vulnerability and courage, and willingness to be guided by those different than ourselves, even—maybe especially—when it’s uncomfortable.

Inclusion asks that our shared environments, whether they be public environments or political environments or work environments, are safe and accessible for all people to exist and tell their stories in. At its most basic level, inclusion simply demands tolerance. If tolerance means accepting others to the extent of not engaging in speech or action that harms them, but also doesn’t ask for celebrating them, we’re not going to sing about it, but we’ll honestly take it. It’s a good enough starting point, and realistically it’s all we can expect from some folks. We hope most will go further, but to expect more than tolerance would lead us down the path of legislating the beliefs of others. Even assuming the most noble intent, this is a tactic that is dehumanizing and it does not work. We can’t use the tools of the oppressor in pursuit of liberation.

Going deeper than tolerance, more genuine inclusion means actively recognizing and rectifying the systemic barriers that prevent certain spaces from being safe and accessible to some people in the first place. This benefits from examining intricate relationships between history, privilege and oppression, human neurology and behavior, how power works and is wielded, and our own positionality/ies among these and other complex dynamics. If this makes inclusion sound more like an ongoing and aspirational journey rather than a destination, that’s because it is. It takes a lot of learning, unlearning, and persistent allyship to embrace inclusion. Inclusion is a slow and active process that moves across generations; the arc of the moral universe.

Despite these lofty ambitions, inclusion also has some problematic ideas associated with it that warrant critical conversation. For example, the word itself indicates division: if we’re speaking of inclusion, what are we including people in? Do all people need or want to be “included” in whatever it is? Who gets to do the including or excluding? Inclusion is dangerously close to gatekeeping, and we need to be very careful not to allow these lines to get blurred.

Inclusion can and has also been tokenized. It’s very easy to say, “All are welcome here! This is a safe space!” while still engaging in practices that harm others, ranging from microaggressions to downright exclusion. This shouldn’t be taken to mean that making inclusive spaces becomes an impossibly utopic task; instead, it means that places that claim to be inclusive also need to be responsive when they learn that that they are engaging in harmful practices. An ongoing journey. Too often when “inclusive” spaces are called upon to revisit their alleged inclusiveness, the immediate response is defensiveness and closing rather than responsiveness and opening. Perhaps ironic given their missions, Universities and State Government are especially culpable of this.

For those struggling with the idea of inclusion, one solution is to seek ways to dispel personal power in order to open up space for real and responsive listening. This is hard work; it asks us to let go of ego, be extremely vulnerable, and in some cases abandon our own personal comfort, remembering that comfort is different than safety. In personal settings, this means creating authentic space for deep trust and open communication, which I believe can be partially provided by many of the principles and practices of Motivational Interviewing (MI). In professional settings, this means ensuring that leadership decisions and organizational policies are actionably informed by cultural humility and trauma-informed servant leadership—which inherently means including people across all bands of organizational power and diverse backgrounds in setting those leadership practices and organizational norms in the first place.

Inclusion in community settings is more complex. Unique community approaches that honor cultural values while also providing room for listening to all members’ voices can’t be neatly packaged into one recommendation, and it would be culturally unhumble to suggest that community leaders let go of power, especially here in New Mexico. Ultimately it is up to communities and their individual members themselves to collaboratively define how they include voices.

On a slightly different note, it’s also critical that nondominant communities gain and/or retain their ability decide how and when to exclude certain voices. This might strike as completely contrary to everything else written here, but allow me to share a personal example to illustrate: as somebody with just over five years of sobriety, if I go to a closed Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, I really do not want anyone who hasn’t struggled with addiction in that room. For them to be there would make it less safe for me to be there. There are just some things they might not get (sorry “normies!”). Not all AA spaces are closed, but if some weren’t, I can’t confidently say I would still be sober today. And if somebody was listening in on my meetings with my sponsor, I definitely wouldn’t be.

This ability to responsively define space should apply to all communities, although it has been a violently difficult and ongoing journey that should not be taken for granted—a sentence I write comfortably sitting on land that was viciously stolen and abused not that many years ago in the grand scheme of things.

Where Some Iterations of DEI Went Wrong

While DEI has undoubtedly been under attack, failing to acknowledge where DEI went wrong under its own heading in recent years would doom it to repeated struggle. Part of why manifesting Equity and Inclusion across Diverse peoples takes a long time is because it’s an imperfect process that requires constant learning and refinement. The best we can do is to aim for progress instead of perfection. Not all proponents of DEI supported the below outcomes, and some of these outcomes got muddled in from the outside. They’re still worth commenting on so that we can learn from them.

Cancel Culture

Cancel culture believes in ends-before-means social accountability, and it wields shame and muzzles as its primary weapons. While many of us working in DEI have long recognized that these are unsuitable approaches and tools for the work of connection, shared empowerment, and growth, others under the headings of DEI and social justice have undoubtedly sought catharsis through this socially violent form of exclusion. Aside from using means that are counterproductive to the ends that DEI aims to achieve, cancel culture also fails practically as a strategy. It just doesn’t work; silencing even those with seemingly supreme power simply gives them a platform to claim victimhood and retreat into an echo chamber. Cutting off communication with those who hold different views is not the path forward.

That does not mean that we need to entertain ideologies or actions that espouse harm. We can use our intellectual and emotional intelligences, as well as our own self-awareness of what is culturally safe and what is not, to choose when to engage and when not to. We can disagree passionately, vehemently, and without apology. We can still be cautious about false allies and the type of white liberalism that Malcolm X warned us about. Silencing and ostracizing, though, make it easier to obscure the truth, not harder. That’s the approach of divisive factionalism, not shared liberation.

Shame and Personalization Instead of Systems Thinking

DEI in 2025 can also learn from past mistakes of personalizing and causing shame in its approach to complex, challenging, and uncomfortable truths. There is an ocean of difference between discomfort and shame, and the latter is rarely an effective motivator for growth.

Before taking on shame, a word on comfort. Comfort is a privilege, not a choice available to all, and discomfort is oftentimes a healthy and normal part of the human experience. This is true both literally and figuratively; there’s a reason we have the terms “growing pains” and “no pain no gain.” People who have access to and/or find ways to cope and persist through the pain of adversity often report what they have learned, how they have grown, and the new perspective they have as a result. Making meaning is the sixth stage of grief. It is ironic that many of those who claim society has gotten soft are the very same people who cannot tolerate the slightest amount of cultural discomfort.

DEI should not and cannot back down on how it approaches feelings of comfort, while simultaneously being very careful to ensure that there is safe space created for that discomfort to exist and breathe without counterproductively turning into defensiveness and resistance.

Defensiveness and resistance are common in the work of DEI; they’re a part of the learning and unlearning process, and they’re navigable with a properly humanizing approach. When shame starts to inadvertently enter the space of learning to be culturally humble, however—or, worse, when it’s actively leveraged as a tool—it enters as an enemy of shared growth and liberation.

So how do we hold both truths at the same time: the critical importance of holding space for meaningful and healthy discomfort balanced against the critical importance of not triggering dehumanizing shame? Brené Brown and others who have researched similar topics give us clues, as they have articulated helpful differences between guilt (“I did something bad”) and shame (“I am bad”).

Guilt is an unpleasant experience of personal responsibility based on feeling as though one has done something that goes against their own or shared values; this could be a mistake, an accident, or getting caught up in the heat of the moment. Guilt is a form of discomfort; it is not related to identity, but to actions, and just like all forms of discomfort, guilt can be oriented towards learning and growth. The actions that lead to guilt can also almost always be repaired when restorative approaches are followed, leading to healing. Guilt, if sensitively handled, does not necessarily stand in the way of growth. It is a barrier, and while I would never advocate for intentionally triggering guilt, if feelings of guilt arise during the work of DEI, it is not the end of the path.

Shame, on the other hand, gets tied to the core of who we are. It treats labels and people as one and the same. It says entire individuals or communities or parts of them are bad in and of themselves, and that they need to fix themselves—or be fixed or ostracized. It leads to feelings of defensiveness and self-loathing that are extremely difficult to engage and move. Shame is static and dehumanizing, telling people: “you’ll never get there,” “you just can’t,” and “don’t even try.” It’s the approach of closing possibility instead of opening it, and it is incompatible with genuine DEI work.

An anecdote for this topic: many years ago, when I was working as an eighth-grade teacher, I had a student of mine hesitantly approach and ask me, “am I bad for being white?” He had begun to attach shame to a piece of his identity over which he has no control (the lottery of birth). He wasn’t just uncomfortable, he was scared. I’ll never know what prompted the question—whether it was social media or a bully or another educator—but I do know that it was not helpful for this child, and it was not helpful for the work of DEI, for him to be feeling like he was inherently bad or wrong because of who he is: a categorical lose-lose. He can’t change being white and shouldn’t want to and being made to feel that way is irresponsible at best and psychologically damaging at worst. His remaining option after being made to feel that way was to close off and ask another white man (me) for validation. I won’t share my conversation with this student, but I was able to thankfully help him feel a bit better. But the point isn’t about me or him really, the point is that shame is a violent weapon, not a helpful tool. This applies to any other races or pieces of identity that one might choose outside of my personal example.

Power and Pushing Too Hard

Dominant power is dominant because it’s good at being dominant. It concedes nothing without demand, but it’s also adapted clever strategies for dismissing demand, leaving a very narrow path for catalyzing change.

The best articulation of power’s ability to refute challenge that I’ve encountered comes from Judith Butler. She argues that in order to exercise agency and effect change in contemporary society, people must work within the power structures to which they are subject, and take the risks associated with assuming pieces of this power and reasserting it in a way that alters its demands.

Pushing at power from inside its boundaries in this way can be frustrating and challenging, but it does appear to be the best approach because of how easy it is for power to dismiss challenge that comes from the outside. Butler explains that assuming and reasserting power in a truly transformative way, even from within its own boundaries and tactics, entails risk for a subject, for “if one fails to reinstate the norm ‘in the right way,’ one becomes subject to further sanction” by society, which may no longer recognize the individual as an identifiable subject, but instead as socially dead, (28-29). Basically, push too hard from the outside, or even the wrong way from the inside, and it’s really easy for dominant power to paint you as “unreasonable,” or “angry,” or “unstable,” or “dangerous;” hysterics and looters and deviants and other labels, usually with some stereotyping discriminatory flavor sprinkled throughout, that serve to silence and outcast those who apparently don’t belong as a part of “civil society.” Socially dead. Another form of cancellation as dominant power reconsolidates with fewer “reasonable” challengers.

The lesson here is not to stop pushing. It’s not to stop resisting or protesting or speaking truth to power when the time calls for it. Instead, it’s to be strategic and thoughtful about how and when to engage, and when to disengage. This calls for using emotional intelligence and self-awareness as to the when and where of applying any of DEI’s approaches, prodding at the limits of power from the inside in ways that we can access. This is aided by allies who represent pieces of dominant power, and is much more effective locally, because we tend to understand and be able to navigate local power structures better than those that are far removed from our daily experience. Protests that target local funding of overseas conflict will be much more effective in creating any meaningful and lasting impact than those that target Middle Eastern governments or overseas peoples themselves.

We need to study the terrain of power—its patterns of dismissal, its reflexive gatekeeping, its hunger for plausible deniability—and decide precisely how, when, and where to intervene. This asks for coordination and working together. Sustainable resistance often requires a layered approach: simultaneous inward navigation and outward disruption, coalition building and solo dissent, cultural fluency and deliberate rupture. Testing the limits and sensing when we’re pushing a touch too hard so that we don’t get dismissed—again.

Pushing power from the inside or as an ally also can’t be performative; virtue signaling for likes is far too common, and often is based on flashy visibility rather than strategic movement towards change. It corrupts the message, driving it into the space of personal glorification. The people dousing historical artwork in paint and oil to advocate for the environment are probably doing more to push people, especially people with money and power, away from their cause than towards it.

This isn’t a call to temper urgency, but instead a request to strategically calibrate force in order to increase the likelihood that a message survives long enough to seed change. To push in ways that expand the boundaries rather than cause them to snap shut. And perhaps most importantly, it’s a reminder that the goal isn’t just to destabilize power, it’s to reimagine the frameworks that give it shape entirely. Not to become dominant, but to make dominance irrelevant.

Weaponizing Identity and The Oppression Olympics

A particularly insidious current in some DEI circles, the destruction caused by people twisting DEI’s message to weaponize their own identities against others cannot be overstated. These are folks who insist upon playing the Oppression Olympics, seemingly competing for who has it “worse off.” They use this self-victimization to dismiss the adversity of other humans, claiming things like their cause is the only one that really matters. These are also often the language police, dictating how others ought express themselves down to the semantic level, regardless of local cultural context.

Dominant power absolutely loves this. The Oppression Olympics are its favorite TV show, because it knows that there is only one winner in the Oppression Olympics: itself. And it just gets to sit back and watch. Nothing easier in the world than letting divide-and-conquer play out automatically. Dominant power knows that when its enemy is making a mistake, it should let it.

People who play the Oppression Olympics not only shut out the voices of others, they also typically do so at their own expense. They create division instead of forging alliance, pushing people away from empathizing with them and allying with them. They distract from the usually shared structural barriers that underly the systemic adversity and oppression of nondominant communities. They enable divisive factionalism, doing the work of dominant power for it.

It would be unfair to say that most people who compete in the Oppression Olympics do so deliberately. I don’t think that’s the case. There is a notable quirk, though, that many who do engage in this destructive behavior occupy at least one very visible feature of dominant identity, oftentimes race, while also holding other pieces of subjugated identity, whether visible or not, within themselves. That’s intersectionality for you. In this case, playing the Oppression Olympics sometimes becomes a self-soothing deflection that allows people to abandon responsibility or feelings of guilt (see the work of Robin DiAngelo on white guilt) for the dominant power structures they do support, whether intentionally or not. By grabbing the reins of the conversation, even in environments specifically slated to discuss other topics, they get to avoid responsibility for their role in the subjugation of others. This isn’t a culturally humble approach, and it damages the cause for everyone.

These folks still have a lot of learning to do about self and others, as do we all, and at the same time it is critically important to heed the cautions above and not cultivate feelings of shame in them. That feeds back into the same self-defense mechanism that causes this harm in the first place. We can only hope to move people forward together by naming this behavior when we see it, compassionately and from the spirit of shared growth.

The Way Forward: Responsible Stewardship of DEI in 2025

I’m sure there are many paths forward from where we currently find ourselves, and I invite conversation from others on what these might look like. Below I share a few of my own thoughts on what will help move DEI forward to be reclaimed as a space of meaningful engagement and growth.

Reclaiming Language and Meaning

One of the main weapons of power and dominance is contorting language and meaning to be threatening, manipulating peoples’ biological hardwiring to be fearful of the unfamiliar. It’s an effective and easy and time-honored tactic, as described earlier, which makes sense: ideas make excellent specters for carrying fear—after all, they can’t defend themselves. That’s where those who still stand on the frontlines of creating a more equitable world come in. We need to work together to reclaim language and meaning around DEI. That has been, in large part, one of my purposes in writing this piece.

DEI isn’t a specter, it’s an acronym. It stands for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. These aren’t threatening words, and they don’t represent dangerous ideas (except maybe towards a select few exceedingly powerful and wealthy individuals, not communities, and those folks will be just fine). When properly stewarded by responsible educators and allies, DEI doesn’t force anything upon anyone; in fact, almost everyone already accepts each of its core tenets to some extent. Accordingly, DEI initiatives in 2025 ought to extend an invitation to engage in self-discovery alongside others looking to better themselves and their world. It's a shared journey of growth.

It’s important not to interpret the work of reclaiming language as doubling down on tendencies such as policing language. This is because policing language closes conversation instead of opening it, and because reclaiming language and meaning is especially effective when grounded in local context and culture, where things like language are fluid. That’s why it’s language and meaning. Outside of calling out directly harmful language, what's more important than semantics is a set of consistent principles that underly the work we do.

Fortunately, we have those principles: diversity, equity, and inclusion. Different language about or local interpretations of these tenets are not only acceptable, but they should also be encouraged. What matters is beneath: the truth that all people have honor and dignity and worth, the truth that the world is unequal and the need for equity to tear down the structural barriers that unjustly prevent some from living their lives with safety and dignity and access and agency, and the truth that we have the shared power to engage in the lifelong journey of working alongside each other to create a more inclusive world for all of us. This is the setting where even those who actively wield dominant power may begin to see the truth that their oppression of others is one of the worst perpetuations of self-harm that they could carry out.

If we are strategic about how we confront power, understand where the limits of shame and guilt lie, and practice what we preach by using humanizing approaches instead of silencing or policing or competing in the Oppression Olympics, the work of DEI is enabled even further because its practices will reflect its meaning, instead of having them run in grating opposition to each other.

Shifting DEI Training to Lean into Self-Awareness, Growth, and Storytelling

Too many institutions, from schools and universities to enormous private corporations to local government, capitalized on the trendy momentum of DEI as a selling point rather than an authentic pursuit. The result was predictable: dubiously qualified DEI training with flashy corporatized logos and slogans popped up everywhere, providing visible lip-service to a worthwhile pursuit that was then corrupted by irresponsible stewardship. Nothing more than an advertisement veiled in moral superiority. These are the “check-the-box” experiences that, whether explicitly or implicitly, disingenuously profess that a 2-hour workshop is enough to shift power structures and systemic barriers that have existed for centuries. Oftentimes, these “experiences” did more harm than good.

I won’t offer implicit bias training without first spending at least a couple hours engaging folks in reflection and storytelling about their own identities, aiming to cultivate some self-awareness and group empathy. Being seen and validated is a universal human need, and jumping straight to pointing out all the ways that people manifest harm, even subconsciously, is the path to shame and defensiveness. Aside from being at odds with the spirit of DEI, it’s also neurologically impossible to learn when triggered in a shame state.

To reclaim the narrative of DEI in the educational space, one of the best ways to start is the simplest: let people tell their stories, if they are safe and able to do so. Good facilitators will create space that balances and honors all voices, and people resonate more with stories from another human in shared space than they do with complex sets of academic jargon or woke rules, especially if they can see pieces of themselves within those stories. Storytelling allows folks to both see others and safely be seen. This is where real empathy is built, which is foundational in embracing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

Embedded within all of this is the idea that DEI learning takes time, consistency, oscillation between internal processing and external experience, and this timeline is not fixed for anyone. Limited experiences like one-off workshops can open the door to deeper understandings, but these experiences have the responsibility to explicitly name that the real work happens out there, and that genuine engagement with this work involves an ongoing pursuit that no single workshop (or set of workshops) can ever fully teach. That’s why it’s cultural humility, not cultural competence; we don’t master it, we grow in it.

Plugging Our Services (Just Being Honest)

If the ideas in this post resonated with you, inspired questions, caused confusion, or stimulated emotions, we'd love the chance to chat with you about it. When it comes to DEI training, as with all of our trainings, we fully embrace our culturally responsive approach. We would be honored to learn more about you and your community so that we can best serve your needs. And we will live up to what we've written here; if we can't deliver authentic DEI training for some reason, we will let you know and steer you in the best direction we can without taking advantage of you.

We offer professional development that goes deeper than what you're used to. Our trainings in Motivational Interviewing, leadership, education, public health, and DEI are designed to help professionals embody person-centeredness while deepening their cultural humility.

Whether you're a clinician, educator, supervisor, or community leader, we’ll work with you to create learning experiences that are engaging, inclusive, and tailored to your context. Our goal is to help you build trust, evoke change, and foster transformation that lasts.

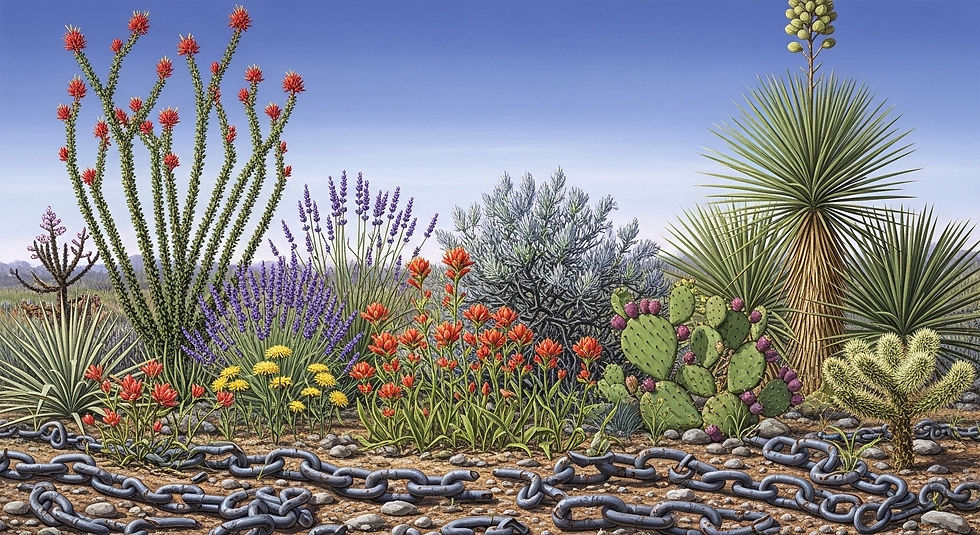

Visit www.ocotillotraining.com to learn more or reach out to explore how we can support your team’s growth. We’re honored to walk alongside you.

Comments